Better bike lights

We’ve previously covered in AutoSpeed building your own high quality bike head- and tail-lights. For my money the best design of DIY headlight was the one covered here – it’s super-bright, has a broad beam that has excellent penetration, and is durable.

However, there have been two problems will all the light systems we’ve covered: the control electronics, and the battery.

To efficiently run high intensity LEDs you need a DC/DC converter that maintains LED current as battery voltage falls. Furthermore, an indication of battery level is important. Finally, it is best if flashing and steady modes are available. Doing these things with DIY electronics is of course possible (and we’ve previously covered some techniques for making your own) but the end result adds up in cost and size.

And batteries? To build your own pack that’s waterproof and compact is a harder ask than it first sounds – and then, what about a charger? In fact, I’ve tended for my own systems to go back to heavy and relatively inefficient sealed lead-acid (SLA) batteries – despite their size and weight, they’re easy to charge and come pre-packaged.

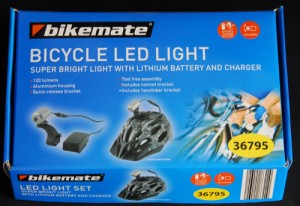

But things are rapidly changing. The other day I bought from Aldi (and unfortunately they’ll almost certainly all be gone by the time you read this) a bike headlight system.

It comprises a 3W LED headlight, 2 amp-hour lithium battery pack, mains-powered charger and assorted brackets for mounting the lights and pack. The system has switchable full power, half power and flashing modes. A battery level indicating LED is also fitted.

I have been watching bike lighting systems very closely for years, and I can say with some confidence that a year ago, a system just like this would have cost well over AUD$100.

The Aldi price? Originally $30 and on special at $20!

I bought one set and tested it. Then, on the basis of those tests, I went back and bought another four sets!

The real beauty of the systems is that the headlight can be easily pulled apart. Doing this reveals the use of a standard ‘star’ (eg Luxeon or Cree style) LED. In turn that means the LED can be changed to whatever colour you want – so in one system I have swapped-in a red tail light LED. (Bright? You’d better believe it!)

The smart LED control electronics can also be easily wired to a non-standard light. So I use one system to power the original glass-and-stainless steel 3W headlight I built in the story referenced at the beginning of this piece.

Are the results good?

Especially with some modifications, for the price I think they’re unbeatable.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.