It’s been cold hereabouts, and I have been doing some more on-road tuning of my MoTeC-equipped, turbo Honda Insight.

(But before I get to the subject of this column, a point on the DIY tuning of programmable engine management. In short, it’s the best fun-for-$ expenditure you can ever make on a car.

Why? Because after you’ve bought and fitted a system, you’ve just gained a pastime you can do for literally ever. There is always – always! – a tuning change you can make that will cause the car drive fractionally better in a given situation, or to develop slightly more power, or to use a little less fuel.

In short, buy programmable management and you’ll never need another hobby or leisure activity!)

So anyway, this time I had the car on 98RON and there was an ambient temp of 5 – 10 degrees C.

Over the last two years I’d have tuned the ignition timing maps on this car for literally hundreds of hours. That might seem to indicate that I’m rather slow at it, but in fact more accurately reflects the statements above about gains always being able to be made – and also the fact that the little Honda is very sensitive to ignition timing variations.

As an example of the latter, it’s one of the very few cars that I know of that requires some negative timing figures if it is to avoid detonation. That’s especially the case at low revs and when only one intake valve per cylinder is working (ie VTEC is off), so giving very high combustion chamber swirl.

I do the on-road tuning of the ignition timing using a microphone temporarily mounted in the engine bay (clipping it to the throttle cable works well). This microphone feeds a small amplifier and I listen on headphones. With this system I can not only clearly hear detonation, but I can also hear the harsher edge the engine develops just before detonation.

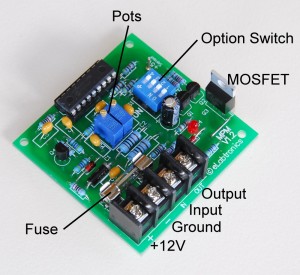

In addition to the headphones – and the laptop on the passenger seat – I also have another trick up my sleeve. A dashboard-mounted knob allows instant variation in ignition timing of plus/minus 10 degrees.

So I drive along (lots and lots of empty country roads around here), listening to the engine through the amplified headphones. I might be at 2000 rpm, full throttle in 4th gear, the engine just coming onto boost and lugging hard up a hill. VTEC is switched on. (So that the engine will readily accept boost pressure, I have the engine switch to two-valves-per-cylinder operation from 1750 rpm upwards at full throttle. The engine doesn’t like it so much if only one-valve operation is occurring as it comes onto boost – in this non-VTEC mode, I have heard turbo compressor surge.)

Anyway, in these conditions, where change is occurring relatively slowly, I manually advance the timing with the dash knob and listen carefully. If the car clearly goes harder (almost always) and there’s no sign of detonation (or its precursor sounds), I pull over and add some timing at that spot overall ignition timing map. Then repeat the process….

Now you know why it takes me so long!

Anyway, finally to the point of this column.

As with all programmable management systems, the M400 has a base timing map (it uses RPM and MAP axes) and then a series of correction maps. These corrections include coolant temperature and intake air temp. Because, as I’ve said, the Honda is very sensitive to timing variations, I use all these correction maps.

Let’s take a look at intake air temp – and how I influence it.

I regulate intake air temp by using a water/air intercooler and variable pump speed. If the intake air temp is below 35 degrees C, the pump stays off. Depending also on throttle position, as the intake air temp rises above that figure, pump speed increases. Together with the effect of the thermal mass of water within the heat exchanger, the upshot is that in nearly all conditions of ambient temperature and boost, the intake air temp stays within the range of 20 – 50 degrees C.

Initially, I’d intended to aim at an intake air temp of around 45 degrees C (the higher temp better for fuel atomisation and so fuel economy), but I found that to avoid detonation, timing had to be retarded at this intake air temp. I then reconfigured the water/air intercooler pump map (ie I turned the pump on earlier) to aim at an intake air temp of around 35 degrees C.

So, all well and good. On this basis, the main ignition timing map would be configured optimally for 35 degrees C, and the intake air temp correction map would knock off timing as the temp rose above this.

Hmm, but what about when it is very cold, like it has been over the last few days? I’ve seen intake air temps lower than I’d ever planned – around 25 degrees. The intercooler water pump is off, but the air entering the turbo is so cold that even with spurts of boost, the water within the intercooler heat exchanger is staying at less than 35 degrees.

And in these conditions I’ve been hearing precursor sounds of detonation through my headphones.

Is it because the density of air (and so cylinder filling charge) is greater, resulting in higher combustion pressures? That is, the greater mass of air (more likelihood of detonation) is more than offsetting the colder air (less likelihood of detonation)? And so do I pull back timing at lower intake air temps (ie less than 35 degrees C) as well as at higher intake air temps (above 35 degrees C)?

And do I therefore accept that, in the real world, the engine will probably never be running the timing as specified in the main chart – after all, while intake air temp might occasionally be at 35 degrees C, stopped at traffic lights in might be 40 degrees, and down a long country road hill it might be 30 degrees – and so on…

And how do I correctly tune this intake air temp correction map? After all, to do it accurately I’d need road test ambient temps that range from -10 degrees C to plus 50 degrees C.

And, thinking about that, I have in fact tuned at the high intake air temps. Early in the tuning process, in the middle of summer and with an ambient of about 35 degrees C, I can remember doing repeated 0 – 160 km/h runs, flat out and working the little car as hard as I dared. I was tuning the high temp ignition timing correction chart (and also revising how much boost gets pulled out in these conditions – another variable!).

Looking out the window as I type this early on a Sunday morning, it’s frosty and foggy, about 0 degrees C. I should, I think, get away from this desk and hit the road for some tuning…

It’s a process that will literally never be finished.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.