When wheels steer themselves

I thought that the idea that car wheels just went up and down over bumps, and were steered only when the driver turned the steering wheel, was pretty passé.

Passive ‘steer’ systems have been in production cars for many years, normally of the rear end.

In broad brush strokes, the systems work like this: The rear bushes are set with differing stiffnesses in different planes, such that when the wheel is subjected to a lateral force (as it is in cornering), it no longer remains parallel with the car’s long axis – that is, it steers.

For example, rear wheel compliance steer is often set to give toe-in, thus settling the cornering car.

The original Mazda MX5 / Miata had such a system. (It’s worth pointing out that the MX5 is generally regarded as one of the best handling, relatively cheap, cars ever released.) In their 1989 book MX-5 – the rebirth of the sports car in the new Mazda MX5, Jack Yamaguchi and Jonathon Thompson write:

No Mazda rear suspension is complete without some form of self-correcting geometry, as have been seen in the fwd 323 and 626’s TTL (Twin Trapezoidal Links), the 929’s E-links and the RX-7’s complex DTSS. The MX-5 double wishbones are no exception, though to a lesser degree. The designers need not worry about camber changes; a recognized virtue of the unequal length A-arm suspension is the admirable ability to maintain the tires’ contact area true to the road surface, attaining a near-zero camber change.

So the chassis designers’ efforts were directed at obtaining a desired amount of toe-in attitude that improves vehicle stability in such maneuvers as spirited cornering and rapid lane changes. Toe-in was to be introduced when the suspension is subjected to lateral force, not to accelerative or braking force. They considered that the MX-5 with its configuration, weight and suspension, would have sound basic handling characteristics, and the lateral reaction would be all it would require to further enhance its vehicle dynamics.

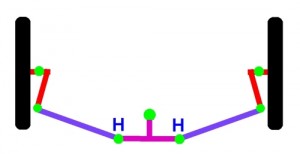

The lower H arm’s wheel-side pivots, which carry the suspension upright, have rubber bushings of different elasticity rates. The rear pivot is on a firmer rubber bushing than the front. The front rubber bushing deforms more under load induced by lateral force, and introduces an appropriate amount of wheel toe-in, which is in the final production tune a fraction of a degree.

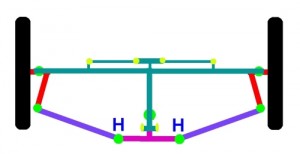

Pretty well all current front-wheel drive cars have some form of passive rear wheel steering. The Honda Jazz uses a tricky torsion beam rear axle in which, according to Honda, “the amount of roll steer and roll camber has been optimised to deliver steady handling”.

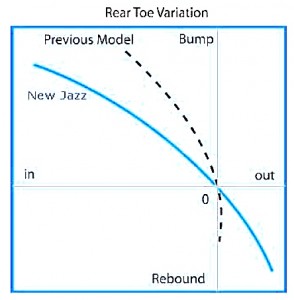

But even better, the company has released graphs showing the toe variation over suspension travel (note: travel, rather than lateral force), with the current model compared with the previous design. As can be clearly seen, in bump (as would occur to the outer wheel when cornering) the Jazz (especially the new model) has an increasing amount of toe-in. Also note the differing shape of the curves in rebound (droop).

And it’s not just the ostensibly non-steered end that uses toe variations built into the suspension design.

Several suspension textbooks that I have suggest that setting up the front, steering wheels for non-zero bump steer can be advantageous. Chassis Engineering by Herb Adams (incidentally, a very simple book much under-rated) states:

Exactly how much bump steer you need on your car is like most suspension settings—a compromise. It is common to set the bump steer so that the front wheels toe-out on a bump. This will make the car feel more stable, because the car will not turn any more than the driver asks.

To understand this effect, picture what would happen if your car had toe-in on bump. As the driver would start a turn, he would feed in a certain amount of steering angle. As the car built up g-forces, the chassis would roll and the outside suspension would compress in the bump direction. If the car had toe-in on bump, the front wheels would start to turn more than the driver asked and his turn radius would get tighter. This would require the driver to make a correction and upset the car’s smooth approach into the turn. The outside tire is considered in this analysis because it carries most of the weight in a turn.

Assuming that your car has the bump steer set so that there is toe-out in the bump direction, the next consideration is how much toe-out. If the car has too much toe-out in bump, the steering can become imprecise, because the suspension will tend to negate what the driver is doing with the steering wheel. Also, if there is too much bump steer, the car will dart around going down the straightaway. A reasonable amount of bump steer would be in the range of .010 to .020 per inch of suspension travel.

Fundamentals of Vehicle Dynamics by Thomas D Gillespie positively describes using roll steer, where the toe variation of the left-hand and right-hand wheel is in the same direction, to alter understeer and oversteer effects.

Even that most exotic of road cars, the McLaren F1, had designed-in passive steer.

Writing in an engineering paper released in 1993, SJ Randle wrote of the front suspension: “Lateral force steer…. was 0.15 degrees/g toe out under a load pushing the contact patch in towards the vehicle centreline. This is a mild understeer characteristic – precisely what we wanted.”

In the case of the rear suspension, “the net result being a mild oversteer characteristic (ie toe out under a force towards the car’s centreline) or around 0.2 degrees/g. We had hoped for an understeer of 0.1 degrees/g.”

Such passive steer suspension behaviour would become especially important in vehicles that, in order to achieve other design aims, have dynamic deficiencies. So for example, a very light car that is aerodynamically neutral in lift, and has a low aero drag, is likely to be susceptible to cross-winds. On bump the passive toe-in of the rear wheels, and toe-out of the front wheels, would help correct this yaw.

Note that adopting these techniques doesn’t require the actual mechanical complexity – or weight – of the suspension systems to change.

But of course it’s quite possible to over-do these effects. As indicated in the quotes above, we’re talking very small steer angle changes. You can’t even transfer the ideas from car to car: the current Honda Jazz steers fine; the Honda City (that apparently uses the Jazz rear suspension) has an unmistakeable, unhappy, ‘rear steer’ feel that is disconcerting on quick lane changes.

But it seems to me that if you are building any bespoke vehicle and simply state point-blank that there should be no bump steer at the front, and no lateral compliance leading to toe changes at the back, you’re taking away a pretty important string from your bow.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.