It’s not in the texbooks…

I am not certain it will happen: I hope so.

As time has passed, the development of ultra light-weight vehicles has become a more important theme for AutoSpeed (and this blog). It’s rather like our longstanding acceptance and enthusiasm for hybrid vehicles: it’s a change in transport architecture that simply makes sense.

(Of course, ultra light-weight vehicles have existed previously – especially just post-World War II with the German and British three wheelers. But over the last 50-odd years, there have been almost none produced.)

So what do I hope will happen? The development of an increasing number of such machines.

If that occurs, especially on an individual constructor level, then people will face some unique and very difficult problems.

We tend to take for granted developed automotive technology, and to see engineering solutions only within that paradigm. But when it comes to ultra light-weight vehicles, that’s simply wrong.

For example, take Ackermann steering – that’s where when cornering, the inner wheel turns at a sharper angle than the outer wheel, resulting in no tyre scrubbing. If I was to say that I have spent the last three days struggling with Ackermann steering, some people would laugh.

“It’s all in the books,” they might say, “just angle to the steering levers inwards like this diagram shows. Been done a million times. Next problem?”

But you see, that solution largely applies only if steering like a car is used – with a steering box or steering rack. And, for ultra lightweight vehicles, both steering boxes and steering racks (or, any currently available, anyway) are way too heavy.

So, how do you achieve Ackermann steering without a steering box or steering rack?

Australian recumbent pedal trike manufacturers Greenspeed have some brilliant solutions. (Disclaimer: my wife sells Greenspeed trikes.)

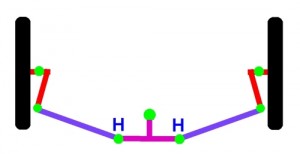

One of their approaches looks like this (the drawing is not to scale.) The system uses wheels that turn on kingpins, two steering tie-rods, and one central linking member turning on an offset pivot. The steering is by handlebars; these connect at the points marked ‘H’ and have a motion that is a combination of both sideways and fore-aft.

This steering system achieves full Ackermann compensation, and requires only four rod-ends and one pivot point. (These are in addition to the two kingpin pivots.)

That is simply an incredibly light and effective steering system.

I recently spent day after day coming up with alternative steering systems for my recumbent pedal trrike – and then building them. It’s quite easy to end up with steering with two kingpins, six rod-ends and two pivot points – typically, about 50 per cent heavier than the Greenspeed system!

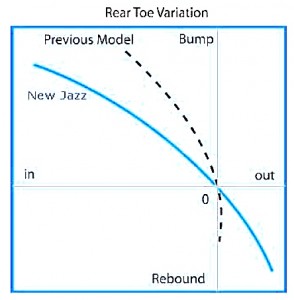

Making things more difficult for me was that, unlike the Greenspeed trikes with the above steering system, my design uses long-travel suspension. And, getting rid of bump steer (ie toe changes with suspension movement) is another nightmare.

Again, people will be thinking only in an automotive paradigm.

“Bump steer? That’s easy – just set the length of the tie-rod so that it’s the same as the distance between lines drawn through the upper and lower ball-joints….” (and so on).

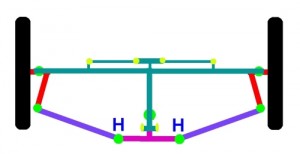

Trouble is, my suspension system doesn’t even have upper and lower ball-joints… Instead, it’s a leading arm, torsion beam, dead axle with a Watts link.

Shown here is (another) rough diagram. In fact, this is pretty well how my system is with Ackerman compensation and zero bump steer. (The really knowledgeable amongst you will have picked a slight error in the drawing.)

The point is that none of this design can take lessons straight out of textbooks – especially automotive textbooks. Of course, the fundamental elements (like the Watts Link, the concept of Akermann steering correction and so on) are all well documented, but in unique applications, actually applying those ideas is another thing entirely.

I am not setting out to suggest I am some kind of hero – all the designers of solar race cars and pedal-powered tadpole trikes have tackled the same ground. But what I am saying is that the challenge is massive, that achieving a good outcome in terms of suspension and steering dynamics – all at a weight that is less than just the steering wheel of a normal car – is difficult beyond belief.

Ackermann and bump steer? If it’s in a typical car textbook, in this class of vehicle it’s usually not the solution…

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.

Julian Edgar, 50, has been writing about car modification and automotive technology for nearly 25 years. He has owned cars with two, three, four, five, six and eight cylinders; single turbo, twin turbo, supercharged, diesel and hybrid electric drivelines. He lists his transport interests as turbocharging, aerodynamics, suspension design and human-powered vehicles.